“Morality is the basis of things and truth is the substance of all morality.” – Mahatma Gandhi

If I asked you to think of fundamental ways that people think about the world, most of you would probably agree that morality is one of the most basic and pervasive lenses that we use to do so. And, as I hope many of you will also agree, it’s probably the most important as well. Morality, essentially, means figuring out the difference between right and wrong. It is the question of how to live a good life; it is the question of which values and virtues are worth fostering; it is the question of how to be a better person and how to make the world a better place.

While writing this blog I tried to think of examples of actions that have nothing to do with morality. I came up with the example of deciding which side of a piece of toast to butter: surely that has nothing to do with right of wrong!?… But then I said, “Wait. Surely one side of the toast must posses the most pleasing soft-and-buttery to crunchy-and-toasty mastication ratio!?!” If that is the case, then that side is better. Therefore that side is the right choice and choosing the other side is wrong.

If it’s possible to find a moral approach to something so insignificant I think it’s safe to say that humans are wired to think of nearly everything in terms of right and wrong.

And we’re not always very good at doing it. Or at even beginning to agree on what right and wrong even are in the first place!

Hume’s Guillotine – You are not always a Scientist

“Knowledge of physical science will not console me for ignorance of morality in time of affliction, but knowledge of morality will always console me for ignorance of physical science.” – Blaise Pascal

Hume’s Guillotine, also called “the Is-Ought Dilemma”, states that there seems to be an insurmountable gap between describing how the world is and prescribing how the world ought to be.

The problem is that we apply our moral reasoning so naturally that we constantly leap past this gap without realizing what we are doing. We are constantly ascribing value to things. But if Hume is right, and we want to be serious about ethical questions, then we need to take a step back to work out how we are justifying this leap from reality to value.

Let’s take an act of torture as an example. We can empirically see that the chemical and electrical activity that occurs in the victim’s brain means that they are going through immense pain and suffering. And then we say that this is horrific; awful; wrong. Yet where was the tangible, testable evidence that this act was wrong? Where is the chemical test for wrongness? Do the laws of physics help? Did we spot 3mg of evil through our microscope? Science tells us this act causes pain but it cannot tell us that pain is wrong; it describes what pain is but cannot prescribe whether it should or should not be caused. That’s a different kind of knowledge entirely. You cannot find morality in a test tube.

So where then do these moral values come from? How are we to work them out? Are we simply making them up? When talking about morality you must leave the moniker of “scientist” behind. Science can certainly inform morality (if we understand how pain–for example–works then we can make more informed judgments about what to do about it), but morality is not reducible to science. Because when you make a moral judgment, much more than scientific knowledge is being used.

“Eureka! I have solved the problem of evil!”

What does God have to do with it?

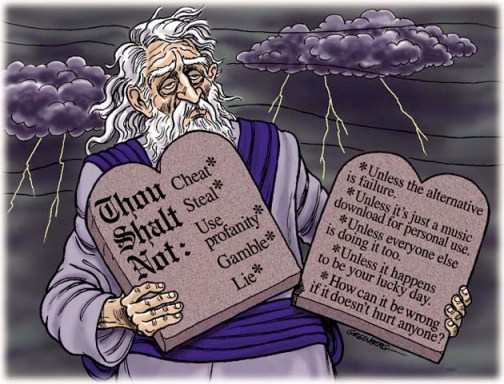

“The greatest tragedy in mankind’s entire history may be the hijacking of morality by religion.” – Arthur C. Clarke

“This is the covenant that I will make with them after those days, says the Lord: I will put my laws in their hearts, and I will write them on their minds” – Heb 10: 16

It would seem that morality is an altogether simpler thing if you believe in God. If God exists, morality is, to paraphrase St. Paul, “written on our hearts”; it is part of the nature of the universe. It is quite a relief to think that morality is not an arbitrary human invention but the natural law of creation, and it is reassuring to think that the injustices of our world will be righted in the world to come.

One of the classic philosophical problems that is raised with this is the question of God and goodness. Is something good because God says it is? Or does God say it because it already is good? Either goodness is arbitrary or it is actually greater than God.*

Does God make judgments like a human does? No. God does not even exist solely within time. God is pure being; perhaps it is helpful to think of it as God’s will and the quality of goodness occurring simultaneously with neither preceding the other. Yet even to think of God as existing within an instant of time is to limit God–but human understanding simply can’t achieve anything else.

Much like the existence of God, our capability to comprehend God’s goodness must have a rather unimpressive limit; before too long you must simply shrug your shoulders and say, “Why does God exist? God just does. Why is God good? God just is.” At the end of the day, such answers are probably no more satisfactory than the alternatives.

*[[You might argue that goodness is arbitrary but that God is consistent. Secondly, the universe has been designed with these values in mind. Therefore, it is a closed system; whatever is outside it is–for all extents and purposes–irrelevant. Thus the question doesn’t matter in the first place.]]

Clowns to the left of me, jokers to the right

Are we TOO Moral?

“Morality is simply the attitude we adopt towards people whom we personally dislike.” – Oscar Wilde

I’ve been listening to a lot of talks by psychologist Steven Pinker recently. One of the talks touched on the content of his newest book which studies human violence. One of the most interesting things that he said in his analyse of violence was that humans are too moral. He points out that most murders, for example, are committed for moral reasons: maybe the victim sexually abused the murderer; maybe they cut them off on the road while driving. When someone is murdered because they “looked at me funny” and therefore “deserved it”, we can see how someone’s sense of morality and justice has gone overboard. If we moralized less, says Pinker, we would be much better off.

Our natural moral inclinations often fail to live up to our considered ideas of what right and wrong should be.

Pinker is a thinker!

Everyone is a Racist

“Morality is the herd-instinct in the individual.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

What way do humans naturally behave? That’s a big question–one which evolutionary psychology tries to answer. I think the “In-Group/Out-Group” theory is a solid one. In short, people like people who are like them, and dislike people who are not. Our in-group typically includes ourselves, our friends, families and loved ones. Our out-group might include people from foreign countries. (I would say it’s not an exact either/or option but rather a spectrum of in-ness/out-ness.)

An easy example that shows this in effect is our willingness to spend money on people. Most of us would be happy to spend €100 on perfume/cologne for our partner. Yet many of us do not give the same amount of money to charity to support people who are starving across the world. €100 would do far more good feeding a starving person than it would making your boyfriend/girlfriend smell nice.

So why do we act this way? It is because we value people subjectively; the closer a person is to you, the more you value them. It is not natural for us to treat people equally.

When we buy new clothes not to keep ourselves warm but to look “well-dressed” we are not providing for any important need. We would not be sacrificing anything significant if we were to continue to wear our old clothes, and give the money to famine relief. By doing so, we would be preventing another person from starving. It follows from what I have said earlier that we ought to give money away, rather than spend it on clothes which we do not need to keep us warm. To do so is not charitable, or generous. – Peter Singer, Famine, Affluence, and Morality, 1972.

How would we act if we valued each person as equal to ourselves?

Furthermore, morality is subjective in the sense that we are often quite happy with changing our minds when we feel that we need to. Our moral sense is flexible to our needs and to the context that we find ourselves in.* While the open-mindedness of this trait can be a good thing, it is easy to point out ways that it is bad too. What is the point of having morality if we abandon it at the first sign of pressure?

*[[Morality is also highly shaped by our culture. Consider attitudes to sexuality, family and marriage. These have changed hugely over the past few decades. But do most of us understand the different perspectives or the values that may be supported or denigrated by them? No. Most of us simply take the values of our culture on board relatively unthinkingly. If we do search for reasons, we can usually content ourselves with ones that justify the position we find ourselves in. If we think morality is a serious issue, we need to be aware of the factors that form our opinions–be they cultural or otherwise. A word of consolation: if you’ve taken the time to read an article like this one, you’re at least taking some steps to doing so!]]

What is a Good kind of Morality?

“A system of morality which is based on relative emotional values is a mere illusion, a thoroughly vulgar conception which has nothing sound in it and nothing true.” – Socrates

When I decided to write this blog I reflected that there’s a circular problem that seems practically unavoidable: how do you decide if a system of morality is good or bad when it is the means of working out how to make such a judgment that is in question? I would imagine that every coherent system is self-justifying! Perhaps it’s a foolish quest.

Nonetheless all of these fundamental questions perplex me. Should a system of morality recognize the reality of human nature and seek to celebrate it? Should it–as Singer would say–push us to be altruistic beyond our basic instincts? Or should it–as Nietzsche would say–push us to break free from the instincts and sympathies that shackle us?

It’s hard to know where to even begin!